THE PSYCHOTHERAPY OF CARL ROGERS:

COMPLETION OF THERAPY

BY WILL STILLWELL

COMPLETION OF THERAPY

In my experience a very rare person is he who offers his presence, and is both open and self-restrictive in his other influences upon me. To me, his presence is a kind of “here-being,” a kind of “grounding” in our proximal space together.

Rogers’ being-present is good-enough. So for me the question, “How does Rogers do it?” becomes, “Who is this person naturally manifesting himself?”

Rogers is his presence, his distinctive individuality who acknowledges and responds to us, who accompanies us in our crises.

I imagine a Rogers’ introspection: “I draw near. I feel myself in your life as-if it is my own living. We are intimate and not merged: we compare our almost-but-never-the-same. You correct your self-perception for yourself and share those corrections with me. You learn to trust your capacity for clarifying and disentangling your living from mine, and from others’ lives.”

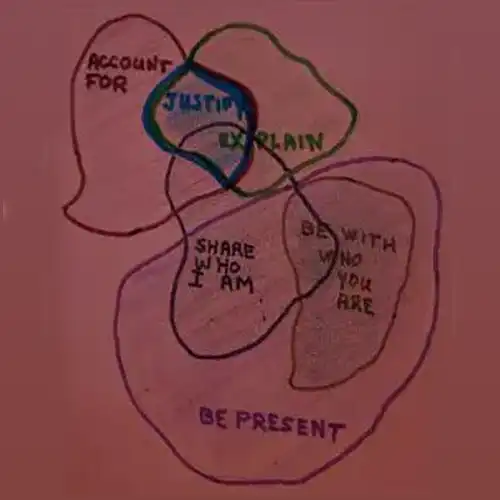

In his therapy, Carl Rogers lives who he is. He has represented – as the whole of the Person-Centered Approach – some of his self-world as he understands it. I believe we who are attracted to this Approach are called to bring our personal learnings, presence, and genuine attitudes to our meetings with our clients. I believe the heart in Rogers’ message is “not what to say or do,” but “who I am; and who you are, and who we are, here.” His practice is being the person he (is, here) (wants-to-be).

In a chapter entitled “This is Me”, Rogers writes of his immense satisfactions learning as he helps by lending his presence with others. He is not self-sacrificial, he is learning life, he is enlarging himself by understanding others through meeting their inner worlds. Rogers’ purpose in therapy is a “relationship of freedom:” freedom to “be,” to “let-be;” “Freedom to Learn.”

“Self” is continual potential brought to “here.” A client’s experiences are retrieved into his “self-structure.” Involvement with an other person’s living experiences and understandings loosens one’s subjectively exclusive fantasies and perceptions of chaos. The client we know as Philip later wrote that being with Rogers loosened one’s ‘schematics.’ Peter Fernald has noticed a ‘physiological’ loosening in clients finishing a session with Rogers. Rogers ‘with’ me and ‘for’ me models a kind of social presence through which I can learn and find my own. My better-structured-self allows me to return to my nexus in a living community.

Rogers built an ‘experimental training’ discipline, a work seeking discovery of his own ‘natural’ way. His way releases him from self-acceptance dependent on favorable external conditions, his way finds his personal responsible self-acceptance.

Rogers discovered himself living toward this, what he called his “organismic” self-regard, bringing into situations his non-self-sacrificing interest and care for the other. Accepting the other person as he is, Rogers experiences his own separate self, and “necessarily experience satisfaction of my own need in accepting myself as I am.”

Here he dwells; his presence is in this trust. It is as if in Rogers’ own experience he might say, “When I am free, who I am – my unconcealed center – emerges: I am empathic, unconditional, genuine. Perhaps in the presence of my inner man we can facilitate your discovery of your freedom, your ‘natural’ way.” Rogers hypothesized that in this we are universally the same. Perhaps in being ourselves, we will discover and value our positive, trustworthy, and constructive core.

What he called “empathy” comes from a long tradition of knowing by verstehen, understanding others by means of their subjective intentions and actions. What he called “unconditional positive regard” is his here-being-with others. And being “genuine” is the main place to stand as he learns.

Rogers’ genuine is genuinely empathic and genuinely regarding of others.

From “genuine” grows truthful “creation.”

“The creative act is an act of integrity:” it manifests beauty, a responsive whole-organism experience of singular pattern coherence. This pattern is an aesthetic – tactility, attraction, intimacy; body-sound-breath – a presence in erotic form. Beauty sensuously intimates pleasures and dangers and expands the desiring self in the presence or absence of an other. He who assumed this immortal power for ancient Greeks is Eros, the beautiful god. He is the first-born; son of Chaos and Aphrodite.

Eros is our fleeting prime mover toward order, he makes the attraction-action that brings and holds people, and things, together: action-knowledge that is organic, thus erotic, sense and soma experience.

The source of Rogers’ art is his imaginatively responsive body – which is good enough – and with which he caresses and feels-out the tender, precious absences emerging as the other brings them into presence. Erotic desire is an uncanny awakening of attraction and trust. What we witness here is a therapeutic manifestation. Beauty is generous erotic unity, but forbidden to us if we do not allow enough our beauty, our own presence.

Rogers’ rather ordinary appearance and manner does not fit with ideals of classical or charismatic beauty. But where a client surrenders to eros with Rogers, he and Rogers both become beautiful – good enough being-here. The client has learned who he is and could be, and what he lacks; that indeed he has failed to feel “good enough” for his life in the extent he has lived in absence. Previously he has been over-filling-in his (temporal) (kairos) present with a deterministic past and future and always. The ‘with-being’ he gains by his whole-person participation in therapy emotionally integrates his present experiences to his self-concept; persistent and disappearing, and meaningful.

Rogers comments, “In some sense the most you can give: be willing to go with them in their own separate feelings as a separate person…let him or her possess his own feelings”

If the therapist permits and does not interfere in her learning process, the client will discover and choose her self, her life-world. A person comes to her own self-approval (or not), she is responsible for her own “good-enough.” “The more I’m open to the realities of life, the less likely I am to rush in.”

“Presence” for Rogers is not an object or state, it is “experience [as a therapist]…in touch with the unknown in me…fully meeting the client.” Through collective participation, the client also may find here his own physical/psychological “presence:” presence in time of Kairos, presence in space of Eros. The kind of presence Steve seeks earlier in the interview is lived out here.

In 1954 Rogers chose the term “unconditional positive regard” for one of his core conditions for therapeutic excellence. Rogers had previously used the description, “deeply respectful, understanding, non-possessive love.” But I think Rogers’ presence cannot be equated to “love.” When I asked him about what to me seemed to be his “love” for a client in an interview he conducted in 1978, he preferred to stay away from that term. In various discussions concerning his understanding of “transference,” a notion begun by Freud’s describing the centrality of affections between patient and therapist, Rogers was dismissive. He acknowledged the importance of clients’ experiences of being non-possessively loved as separate beings, but he did not want to reduce the “feelings” to sexual desire nor focus on the “feelings” that either participant might have for the other separated from all the “feelings” they might experience.

These interviews we’re sampling are from the 1980’s. On other occasions, those not connected to concerns about his “core conditions,” Rogers during this decade was moved to express his feelings between himself and one or another client even more ecstatically, some have said spiritually.

“Our relationship transcends itself, becomes part of something larger”; an “almost ectoplasmic bonding …truly I-Thou…unique persons in tune…” “in line with significant forces of the universe…”

“I and cosmos whole beauty, harmony, love.“…the possibility that there is a lawful reality which is not open to our five senses; a reality in which past, present, and future are intermingled; a reality in which space is not a barrier, and time has disappeared; a reality which can be perceived and known only when we are passively receptive, rather than being bent on knowing.” Perhaps Rogers’ “spirituality” is his sense of movement into a kind of fusion, his dropping empathic separation between himself and an-other. Clearly his theory of psychotherapy is at odds with this interpretation. Ancient Greeks considered such fusion a rare aesthetic, erotic event.

Rogers assumes absolute otherness of the other, the client. This helps each client to accept his own absolute uniqueness. It’s a “curious paradox, when I accept myself as I am, then I change”.

As a client feels his own self-integrity endurance, his therapy interest is served. The therapy relationship has flourished in unequal ‘with-being’ lived here-and-now by the therapist and client. As the therapy draws to a completion Rogers says the client “is experiencing what he is expressing…also experiencing my understanding of it and reaction to it…”

With Rogers, the client assents to receive his own originality. He discovers – to his own shock – Carl Rogers whose authentic presence is felt. A man not only or merely performing his social role; not as a psychological professional, nor bureaucrat nor guru, but a person, a self, an other, here. Something moves between them. I believe that “something” is the client’s attraction to the person of Rogers. But, in expansion and more important, attraction to the newly accessible “Other” – accepted as his own ‘inner’ and/or as that ‘beyond’ self. Invited by Rogers into living their mutual ‘open,’ the client’s wider potential with other human beings opens. He is able to experience a changed context for himself in actual human relation: a sense of security, sanity, caring; and a fuller integration into humanity. He experiences how his healthy self necessitates his satisfactory engagement in his social nexus.

The client’s self-revelations and Rogers’ responses have opened presence in the client’s own inner world. He recognizes their mutual with-ness, he ceases evaluating the contrasts between himself and Rogers. The client has taken responsibility for himself in meeting, and his “matrix of reactions and desires…becomes elastic and transparent”, “limitless without essences and remorse.”

No longer are client and therapist, in Buber’s phrase, “mis-meeting.” Both are making what Buber called the “bold, imaginative swinging” into each other’s life: they are living bodies for each other and for themselves. Rogers is revealed to the client as his partner in the “cosmic dance”: original and personal unique, present beings.

It seems to me the metaphor of “touching” best conveys the (non-physical, erotic) mutuality that Rogers treasured in his therapeutic relationships. I cradle this “touching” in the experience Rogers depicted as organismic self-regard. And he ventured to metaphors of “transcendent” and “spirit” as possible ways to understand the mutuality he sometimes experienced in these meetings. “Spiritual” or “erotic” or neither, Rogers’ profound experiences were anchors to his sense of self and impetus to his search for explanation.

As the participants in these four, one-half hour sessions are fully aware, they have not experienced a whole course of therapy. Perhaps they have opened themselves to their own possibilities in relating through continual renewal rather than simple problem-solving.

Richie and Philip have, perhaps surprisingly, experienced themselves here able to accept their own positive self-evaluation.

Steve and Dadisi entered an environment that allowed space for their emotions and further exploration of their psychological lives.

Carl Rogers’ presence we witness here is not a static, presumably God-like constancy where being and presence is unchanging. It is a psychological availability, conceived in bodies in spatial/tactile proximity. Rogers is con-tingent – in moving relationship and new expression with the changing presence of the client.

“Truth” does not appear as an “answer,” it is embodied in relationship and circumstance.The integral is mutable, but trusted in its process of emergence.This moment, this movement is becoming here, not everywhere and always.

Here he is, Carl Rogers – not a god, not an icon – a man living within a role which he fully inhabits, accepts, contains, and radiates.

Not a god, but good enough as a partner in the cosmic dance.

How does it seem to you?

–

Will Stillwell